Scidmore Book Titles at 1893 World’s Fair

Women’s History Month begins this week. The Center for the Book at the Library of Congress kicked things off things with a presentation March 2 on a new scholarly work, Right Here I See My Own Books. The book describes the woman’s library of 8,000 titles assembled for the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 (officially the Columbian Exposition).

Women’s History Month begins this week. The Center for the Book at the Library of Congress kicked things off things with a presentation March 2 on a new scholarly work, Right Here I See My Own Books. The book describes the woman’s library of 8,000 titles assembled for the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 (officially the Columbian Exposition).

I seemed to recall from my research that Eliza Scidmore reported from the fair. Revisiting my notes, I found an article she wrote for the Aug. 19 issue of Harper’s Bazaar.

It made me wonder whether she had books in the woman’s library. I checked an online list of the titles. And yes, she did! She had three works on display.

8,000 Titles

The exhibit featured Scidmore’s books Alaska: Its Southern Coast and the Sitkan Archipelago (1885) and Jinrikisha Days in Japan (1891). The third work on display, Westward to the Far East, was a travel guide she wrote for the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

Scidmore had published her latest book, Appleton’s Guide-Book to Alaska, only a few weeks before the fair opened. That book appeared too late to be included in the women’s library.

The library of women writers was assembled in the fair’s Women’s Building (shown below). The building was controversial — just as the Women’s Pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia had been. Some women lobbied to have a special area for exhibiting the products of women’s industry. Others protested the segregation of women’s work apart from that of men. Nonetheless, at both events, the women’s buildings became a great source of pride for women.

Women’s Building at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 (Source: Radford University website)

In their Library of Congress presentation, Sarah Wadsworth and Wayne A. Wiegand noted that American women made up the bulk of the authors represented in the 8,000-volume library. But the display also included books by women from other countries. The works spanned several centuries, from the 15th to the 19th centuries.

Japanese Exhibits

When Eliza Scidmore went to Chicago for the fair in 1893, she had already made several trips to Japan. Her Jinrikisha Days in Japan had been published two years earlier. She reported from the fair on Japan’s exhibits.

Japan had been isolated for 200 years when it opened its doors to the outside world in the 1850s. In the decades that followed, Japan participated in several world fairs as an important form of cultural exchange.

Because of wide curiosity about Japan, the country’s exhibits at the 1876 and 1893 world’s fairs became very popular. Fair-goers and “globetrotters” had a keen interest in “Old Japan” — the country’s feudal customs and artistic traditions — just as the country was barreling toward modernization in its Meiji period.

Reporting on Japan’s wares in Chicago, Scidmore noted the move toward production for mass markets. “The commercial progress of the country is more apparent than any artistic progress,” she wrote. While visiting potteries and porcelain factories in Japan the previous autumn, she had observed that everyone seemed preoccupied with making goods for the Chicago fair.

‘Phoenix Temple’

Japan had 14 exhibits in Chicago, scattered throughout the buildings and fairgrounds. Eliza wrote: “If one wishes to see what our Oriental neighbors have done, he must incidentally see the whole fair.”

One building housed densely packed shelves of porcelains, enamels and bronzes. The objects included oversized cloisonné vases , as tall as people, studded with mirrored pieces that reflected the light.

Other displays featured women silk weavers; elaborate embroideries and robes; screens, lacquers and scrolls; miniature landscaped gardens; cryptomeria, bamboo, hinoki and camphor wood in the forestry building; and foodstuffs such as rice.

The Women’s Building contained an exhibit of a Japanese noblewoman’s boudoir. There was a tiny Japanese tea garden, where the tea was served in large Western-style cups. Patrons willing to pay “the superior price” could watch a demonstration of the ancient tea ceremony while seated on cushions.

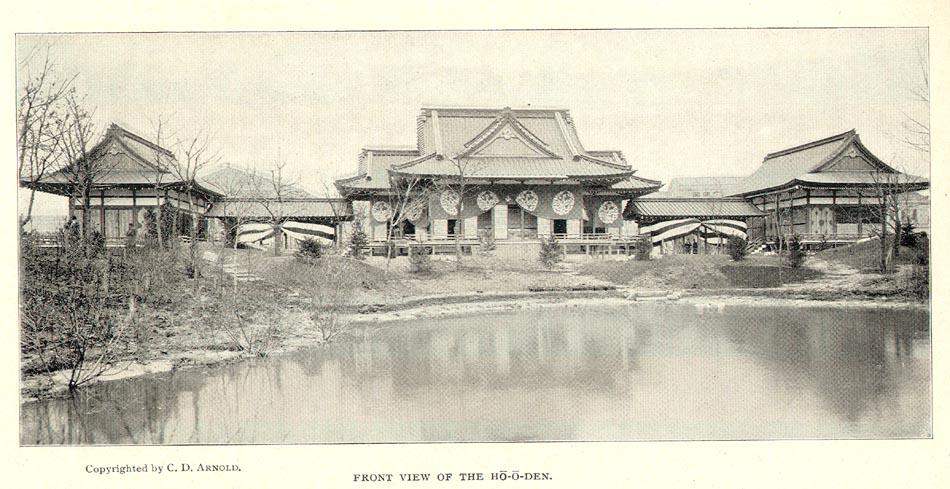

The most popular Japanese exhibit was a replica of an ancient temple. It was named Hō-ō-den, for “Phoenix Temple.” Fair-goers had to cross a red-lacquered bridge to reach it on a wooded island.

Inside, the temple held furnishings and accessories typical of the home life of the Tokugawa shoguns (bafuku). That hereditary line of rulers exercised political control in Japan until the emperor was restored to power in 1868 (known as the Meiji restoration).

Together, the study, dining room and audience room of the temple “are a jewel-box in three compartments,” Eliza told readers in her Harper’s Bazaar article.

Toward a Women’s Museum

A co-sponsor of the book launch at the Library of Congress was the National Women’s History Museum. An effort has been underway since 1996 to have a museum of women’s history built in Washington. The favored spot is adjacent to the National Mall (at 12th Street and Independence Avenue, S.W.).

A lot of high-powered women have put their weight behind the museum. Among them: actress Meryl Streep, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Congresswoman Barbara Mikulski of Maryland.

Even Vogue magazine has gotten behind the cause. Last fall it featured a group portrait, by celebrity photographer Annie Liebowitz, of a dozen leading women advocates for the museum posing on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol.

[…] Scidmore was also at the Chicago fair. But her presence at the 1876 event launched her […]