On Serendipity in Research

Serendipity is like the crack cocaine of research. It gives you a wonderful high.

Serendipity is like the crack cocaine of research. It gives you a wonderful high.

I remember well the first time I came to understand the term. It was in the 1980s, and I was in graduate school at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism. For my science writing class, I interviewed several researchers on campus who were studying different aspects of cystic fibrosis.

Cystic fibrosis is an insidious disease in which a faulty gene and its protein product cause the body to produce a thick, sticky mucus that clogs the lungs and impedes proper digestion. One researcher at Mizzou, a pediatrician, was working to improve clinical observations. A pair of biochemists hoped to develop a reliable diagnostic test for the disease. And another researcher was studying glandular secretions in a rat model.

The dean of the medical school, Charles Lobeck, had followed a hunch about cystic fibrosis early in his career. The lead came from hearing a pharmacologist lecture about his research on the salt glands of marine birds.

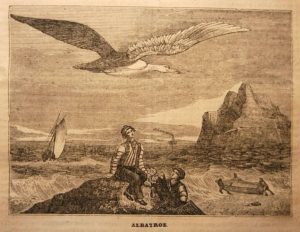

Dr. Lobeck knew that the albatross was said to never touch land, and it made him wonder: How could the bird possibly live, since all animals need water and the sea is so salty? He learned that the albatross has a gland in its nose that enables it to filter out the salt and retain the water.

As a pediatrician, Lobeck was aware that abnormally salty secretions were a characteristic of cystic fibrosis. That realization led to a study of 200 children with the disease to see if a similar mechanism was at play.

The results didn’t pan out. What did happen, however, is that the outcome inspired a new line of studies that helped make his reputation.

“It was serendipity,” he told me. “You start out looking for one thing and find something else.”

I’ve never forgotten his words.

First Lady Helen Taft

I have a favorite serendipitous moment that occurred several months into my research on Eliza Scidmore. I had read that First Lady Helen Taft was amenable to Scidmore’s suggestion of planting cherry trees near the National Mall in Washington because Mrs. Taft herself had lived briefly in Japan. For context, I needed to know: When did she live there, and why? So at the Library of Congress I checked out Mrs. Taft’s memoir, Recollections of Full Years (1914).

The book provided the answer to my question — and a surprise: It includes a passage on Mrs. Taft’s visits in Japan with Eliza Scidmore’s mother!

The elderly Mrs. Scidmore, it seems, achieved celebrity status in the Orient while living there over many years. Mrs. Taft refers to her as “a sort of uncrowned queen of foreign society.” Since then, I’ve discovered that an open house held every year on Mrs. Scidmore’s birthday was quite a big deal in Yokohama society.

The passage thrilled me because it offers some insight into the Scidmores’ life in Japan. Equally important, it helps explain the later familiarity between Eliza Scidmore and Helen Taft that led them to see eye to eye on the planting of cherry trees in Potomac Park.