In St. Louis, Intrepid Women on the Frontier

I had never been to St. Louis until this fall. Funny I should have missed it, as I attended grad school in journalism at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

I had never been to St. Louis until this fall. Funny I should have missed it, as I attended grad school in journalism at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Mizzou classmates and I used to pile into a car and go eat catfish at a tin-ceiling hotel in Booneville. We drove to Kansas City for barbeque at Arthur Bryant’s, which Calvin Trillin made famous in a 1972 article for Playboy.

Certainly I would have remembered visiting the famous gateway arch — if we ever went to St. Louis. But it remained a vague landmark I remember passing on the major east-west highway that runs through St. Louis.

Fortunately, my husband’s recent business trip to St. Louis offered a new destination to explore. Above all, I went to St. Louis looking for traces of Eliza Scidmore, the subject of my book in progress.

Looking for a ‘Sense of Place’

Eliza Scidmore wrote for the Globe-Democrat in St. Louis (as well as other papers). But I wasn’t sure if she spent any time in St. Louis. She did most of her early reporting from Washington, D.C.

The story of Scidmore’s role as the earliest visionary of Washington’s cherry trees dovetailed with the city’s gradual beautification. That movement first gained steam after the Civil War. And St. Louis figured prominently in the story.

Washington had grown so shabby after the war that many Americans petitioned to move the federal capital. St. Louis emerged as a favored spot. For one thing, it was a vibrant, rapidly growing city that seemed to epitomize the shift of American wealth and dynamism toward the West. Besides that, it stood smack in the geographical center of the country.

Of course, the efforts to move the capital never succeeded. President Grant and Congress grew so alarmed by the campaign that they mandated a major makeover of the city. (It was orchestrated by the infamous Alexander “Boss” Shepherd.)

St. Louis continued to flourish. And so did the Globe-Democrat. It was already one of the most important newspapers in the West when Eliza Scidmore joined its network of correspondents.

Like master biographer Robert Caro, I think a “sense of place” helps explain what makes people who they are. So maybe St. Louis would turn up some clues to Scidmore.

I trekked off to the St. Louis Mercantile Museum, housed at the University of Missouri’s St. Louis campus. The museum has the business records of the Globe-Democrat, which ceased publication in 1986. I knew they dated only from the 1920s. Not very helpful for the time period of my book. But I’ve learned, as every researcher does, that serendipity can offer up wonderful surprises when you poke around.

Unfortunately, the results were not very productive. But I did enjoy two fine exhibits while I was there.

Thomas Edison’s 1872 mimeograph machine, on display at the St. Louis Mercantile Museum (Photo: D. Parsell)

Newspaper History

First, I spent several hours in the museum’s very thorough exhibit on the history of journalism in the region.

One delightful discovery: an original mimeograph machine patented by Thomas Edison in the 1870s. It reminded me of the mimeograph machine that lived in the principal’s office at my Catholic school in Marietta, Ohio.

When I was in the eighth grade I started a school “newspaper” using the mimeograph machine. First, I typed up the articles on my mother’s clackety portable typewriter. The sheets were thin pieces of stencil paper, and typos had to be fixed with ink from a tiny bottle. I even remember drawing the “masthead” banner and using a ruler to mark the columns. Then I cranked out the pages on the mimeograph machine.

I went on to become editor of my high school’s paper. But that funny little newspaper from eighth grade seems more vivid after all these years.

Intrepid Women

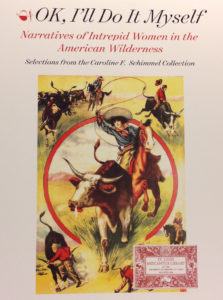

The second exhibit at the Mercantile Musuem was more modest, but totally engrossing. Who could resist the title? “Narratives of Intrepid Women in the American Wilderness.”

The items on display — based on the Caroline F. Schimmel Collection at Penn Libraries described the experiences of about a hundred women who lived or traveled in “untamed” areas. Among the material:

- Accounts of Indian captivity

- Travel diaries

- Field journals of nature writers and illustrators like Celia Thaxter

- Articles and artifacts of female adventurers such as mountaineer Annie Peck and Wild West entertainer Annie Oakley

- Works by authors and writers including Nellie Bly, Helen Hunt Jackson, Willa Cather, Zora Neale Hurston and Ann Patchett (represented by her 2011 book State of Wonder).

Certainly a topical exhibit in this day of “she persisted” and #MeToo.

Noticeably absent: Eliza Scidmore. She didn’t appear, despite her pioneering writings on Alaska in the late 19th century and her newspaper reporting from many parts of the American West.

St. Louis Mercantile Museum (Photo: D. Parsell)

Benton Park in St. Louis

Botanical Garden

Bruce and I both enjoyed our introduction to St. Louis. Our B&B room overlooked Benton Park, with many good restaurants only blocks away.

Maybe it’s because I was raised in the Midwest — in Ohio — but I really liked the vibe of St. Louis.

In another highlight of the trip, I spent a full day at the Missouri Botanical Garden. Even in late fall, a surprising number of plants were in radiant bloom.

The site has a fine Japanese garden, one of the largest in North America. That kept me amused for awhile, because Eliza Scidmore wrote a lot about Japanese gardens and gardening.

A nice fall getaway, indeed.

Photo Gallery

Below, Halloween fever raged at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis on the day I visited.

(Photo: D. Parsell)

Glass sculpture plants by Dale Chihuly rose organically from a tropical pool.

(Photo: Diana Parsell)

Reflecting pool, with the biodome in the background.

(Photo: Diana Parsell)

I love the contrast of this lemon-and-lime tropical foliage with flaming New Guinea impatiens.

(Photo: Diana Parsell)