The Englishman Who Saved Cherry Trees

Cherry blossom viewers love the variety known as “yoshino.” The white petals tinged in pink make up the clouds that encircle the Tidal Basin in Washington every spring.

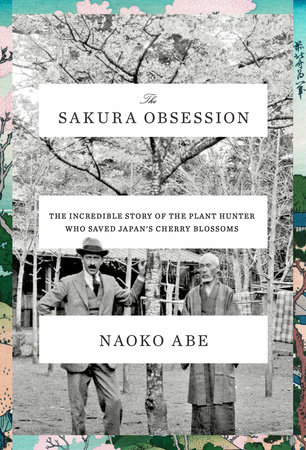

In “The Sakura Obsession,” the author Naoko Abe shows a flip side of that enthusiasm. Her new book tells the story of an Englishman so concerned about the growing fixation with yoshinos that he set out to save other cherry tree varieties.

Collingwood Ingram, born in 1880, gardened passionately at his home in rural England. His fixation with Japan’s most treasured plant earned him the name “Cherry” Ingram.

Ingram first admired “sakura” during his honeymoon in Japan in 1907. After World War I, he started a cherry tree garden and grew many varieties. As the book title suggests, he grew obsessed with cherry trees. He imported seeds and cuttings, and became an expert at cultivating the trees.

In 1926, Collingwood went to Japan to search for new varieties. It stunned him to discover that the country’s diverse botanical heritage of cherry trees was at risk of being lost due to an obsession with yoshinos.

Japan’s ‘Cult’ ofYoshinos

Flowering cherries in Japan grew originally in mountainous areas and other wild places. Over many centuries in feudal Japan, aristocrats devoted themselves to hybridizing and cultivating new varieties.

Hanami, or cherry blossom viewing, became a ritual in Japan as long as a thousand years ago. The pageantry of royal celebrations has been depicted in rich artwork. But hanami wasn’t just for the elite. Every spring, Japanese people from all walks of life turned out to stroll among the trees.

The practice continues, in one of Japan’s most celebrated traditions.

“Hanami,” or cherry blossom viewing, in Ueyno Park, Tokyo,

March 2013 (Photo: D. Parsell)

The Japanese revered cherry blossoms in part because their fragile, short-lived beauty seemed to symbolize the transience of human life, a view in keeping with Buddhist sentiment.

In time, the exceptional beauty of Yoshinos made them a favorite.

In the mid-19th century, when Japan embarked on an ambitious program of changes to transform itself from a feudal society into a modern power, cherry blossoms became a powerful motif of cultural unity for the nation.

When Eliza Scidmore, the subject on my biography in progress, traveled in Japan beginning in the 1880s, she found cherry blossoms everywhere she went. On the caps of military cadets. In tea cakes and other sweets. In clothing and textile designs.

In a darker side of the picture, Naoko Abe explains in her book, cherry blossoms gradually came to serve as a unifying cultural symbol for an increasingly beligerent nationalism in Japan.

By the turn of the century, Western powers were growing alarmed by Japan’s military might. Its victory in wars with two major empires — first China (1894-5) and then Russia (1904-5) — put the world on notice that upstart Japan was a force to be reckoned with.

To outsiders keen to understand the source of Japan’s strength and intense discipline, the answer lay partly in samurai warrior traditions that prized, above all, fealty to the emperor.

In World War II, kamikaze pilots would fly into battle with cherry blossoms painted on the fuselage of their planes, an expression of the sacrifice they were were prepared to make for the nation.

Self-Appointed Savior

After his 1926 trip to Japan, Collingwood Ingram grew single-minded in his attempts to “rescue” Japanese horticulture from the tyranny of devotion to yoshinos. He sent many varieties of Japanese cherry trees to be propagated in gardens around the world.

His campaign included efforts to return a favored variety in his garden, the white-blossomed Taihaku, to its native home.

Over several decades, Ingram became one of the world’s leading experts on cherry trees

Ingram had something of a U.S. counterpart in David Fairchild, a botanist and “plant explorer” at the USDA who was also the subject of a recent book. Like Ingram, Fairchild developed a keen interest in cherry trees during a trip to Japan. He became obsessed with introducing them to U.S. agriculture.

Fortuitously, Fairchild’s interests dovetailed with Scidmore’s determination to see cherry trees planted in Washington’s new Potomac Park. By joining forces, they were able to make that a reality in 1912 with the backing of First Lady Helen Taft.

It took Eliza Scidmore nearly three decades to see her vision realized. But she never gave up on the idea, despite repeated resistance from the men in charge of Washington’s public parks.

Obsession is a strong motivator.