Recalling My Fabulous Glacier Bay Research Trip

Caitlin Campbell in Glacier Bay National Park

(Reposted from August 2018) An email out of the blue from U.S. park ranger Caitlin Campbell sparked my first trip to Alaska this summer, capped by a special experience at Glacier Bay. Caiti first contacted me a year ago after stumbling across the original website and blog I started to chronicle my progress on a biography of Eliza Scidmore.

Caiti and her colleagues at Glacier Bay National Park knew vaguely about Scidmore’s historic travels to Alaska in the 1880s. But they didn’t know much about her life. When Caiti and I arranged to talk, several folks at Glacier Bay joined our conference call.

Caiti’s follow-up email made my day: “Our conversation with you has been the talk of the town this afternoon in Glacier Bay headquarters.” I later did a 90-minute teleconference briefing about Scidmore to Glacier Bay staff as they geared up for the summer tourist season.

Then, in July, I got to see Glacier Bay through Scidmore’s eyes when my husband, Bruce, and I went to Alaska for the first time. I did research at the beautiful new Alaska State Library Archives in Juneau. There, I turned up material on Scidmore I hadn’t found elsewhere.

A Local Legend

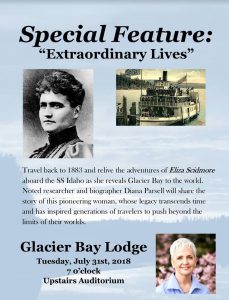

During the trip, I delivered a lecture on Scidmore to an overflow audience at the Glacier Bay Lodge in Gustavus, Alaska.

Many of the people who turned out that night were residents of Gustavus (pop. 450), the gateway to Glacier Bay National Park. Locally, Scidmore is something of a local legend as a female adventurer. One woman in Gustavus dresses as Eliza for various events.

of the people who turned out that night were residents of Gustavus (pop. 450), the gateway to Glacier Bay National Park. Locally, Scidmore is something of a local legend as a female adventurer. One woman in Gustavus dresses as Eliza for various events.

A day after the lecture, I gave a brown-bag lunch briefing to rangers at the park service’s headquarters. Among those attending was Dena Matkin, a marine biologist who named a killer whale for Eliza. “Ruhamah” — Scidmore’s middle name — is one of about a hundred members of the AF Pod of whales in southeastern Alaska.

I organized the trip to accommodate filming in Juneau for an episode of BBC2’s “Great American Railroad Journeys.” My interviewer was Michael Portillo, a former minister of Parliament who hosts the popular travel series. The producers wanted to interview me about Eliza Scidmore’s 1893 book Appleton’s Guide-Book to Alaska.

The producers told me to pack for filming in what they expected to be rainy weather, so I had my rainproof parka and waxed hat on hand. But the weather that day turned out to be a highly untypical 80 degrees!

Filming in Juneau for BBC2’s “Great American Railroad Journeys,” with host Michael Portillo (Photo: Bruce Parsell)

Historic 1883 Voyage

Eliza Scidmore made history when she went to Alaska for the first time in the summer of 1883. She was already a seasoned journalist by then, at age 26.

The United States had owned the territory of Alaska only 16 years, and Americans did not have a favorable impression of the region. Thanks to editorial cartoons lampooning “Seward’s Icebox,” most people pictured a vast tundra covered in ice and snow, populated only by polar bears.

Scidmore knew better. She had followed Alaskan affairs in Washington for years. She also read John Muir’s published accounts of his travels in Alaska, which influenced her desire to see Alaska for herself.

Muir went to Alaska in the summers of 1879 and 1880 to study glaciers. On his first trip he traveled by dugout canoe with Indian guides, on an 800-mile journey took them into the uncharted body of water that was later named Glacier Bay.

Muir helped spark Americans’ interest in seeing Alaska, giving rise to the tourism industry. His campaign to save its wilderness planted the seeds of the U.S. conservation movement, as Alaska author and former park ranger Kim Heacox describes in John Muir and the Ice That Started a Fire.

On the heels of Muir’s travels, Scidmore helped fuel tourism through her 1885 book, Alaska: Its Southern Coast and the Sitkan Archipelago. Based on two reporting trips she made, it’s now considered the first guidebook to Alaska. During her 1883 trip, she and her fellow passengers aboard the mail steamer Idaho became the first tourists to visit Glacier Bay. (See my video of that historic voyage.)

With ranger Caiti Campbell at Glacier Bay National Park, July 2018

Scidmore continued writing about Alaska to the end of the 19th century. She updated her original travelogue into a comprehensive guidebook that remained a standard reference work well into the 20th century. Today a mountain and a glacier and bay in Alaska are named for her.

During the daylong excursion of Glacier Bay that Bruce and I took aboard one of the National Park Service’s tour boats, we sailed past Scidmore Glacier and Bay. Happily, Caiti Campbell was the ranger assigned to our boat that day!

Parallel Travels

Our trip up the bay tracked over Eliza Scidmore’s travels even before we left the docks at Bartlett Cove, where the National Park service has its Glacier Bay headquarters. Bartlett Cove figures prominently in Scidmore’s account of how the captain of her ship, James Carroll, made the decision to sail into the uncharted waters of the bay.

According to Scidmore, Captain Carroll veered off the ship’s usual Alaskan route to deliver supplies to a new trading post and salmon saltery in the area. It was located just inside the mouth of the bay — at Bartlett Cove. Talking with the owner of the trading post, an eccentric white settler named Dick Willoughby, piqued Carroll’s interest in the mighty glacier John Muir had reported seeing to the north.

The next morning, a day in mid-July, broke clear and sunny. That’s not routine weather in the bay, even in mid-summer, as I learned from Caiti. “You picked a great time to come,” she told me. The previous weeks had brought a lot of rain. On Scidmore’s repeat journey to Alaska in the summer of 1884 the ship visited Glacier Bay in heavy mist.

Cruising through the jade-green water of Glacier Bay, we watched mountain goats scrambling up the side of a glacier and bears ambling along shore. (Photo: Diana Parsell)

A thick morning fog shrouded the area as we set off for our daylong trip in Glacier Bay on July 31. Much of the shoreline scenery was obscured, though later in the day we saw bears, mountains goats and a variety of birds. It surprised me to see how jade green the water was in the wake of our boat.

Now and then we passed another ship that seemed strangely marooned in the middle of the bay. Fortunately, access to the bay is limited so the scene wasn’t marred by the presence of the behemoth cruise ships we saw docked in Juneau. Three to six of them arrive there every day, discharging thousands of passengers during the few hours in port.

The fog in Glacier Bay lifted around noon as we headed toward Tarr Inlet, in the far northwestern arm of the bay. The shift seemed to occur quite suddenly as the fog burned away. We sat docked in the inlet about an hour, watching the glacier shed its ice and sea otters bobbing in the water.

The sky was brilliantly blue and clear as we reversed course. The break in the weather offered expansive views of the landscape as we sailed past Scidmore Cut and the glacier behind it.

“Eliza’s glacier” lies on the western side of the bay, near Hugh Miller Inlet. The cut is a narrow passage leading into Scidmore Bay. “I don’t think I’ll ever forget the fog lifting just in time for us to see Scidmore Glacier,” Caiti told me later. “It’s not every day a ranger gets to share a moment like that with someone just as passionate about Glacier Bay’s hidden history.”

I was still feeling pretty high about the tour of the bay when I lectured on Eliza Scidmore that night at the lodge. One of the upsides of the long, hard slog of researching and writing a biography is sharing the findings with people who are excited about the subject.

Soon after I returned home to Washington, Caiti sent a lovely note that capped the pleasure of the trip to Alaska:

“Wow! That really was amazing to have you here in Glacier Bay. … The fact that in just a year we went from thinking, ‘Eliza must have just been some wealthy heiress,’ to now knowing that she was a world-traveled, independent, indefatigable start-up, reminds me of the power of research to unearth voices of forgotten figures. The world needs more Eliza Scidmore!”

Kayakers in tidal channel entering Scidmore Bay. (By QT Luong/TerraGalleria; author of “Treasured Lands: A Photographic Odessey Through America’s National Parks”)

More Photos From Juneau and Glacier Bay

Every year about 400,000 tourists visit Glacier Bay. Rangers board cruise ships and tour boats to provide information on the bay’s history, geology and wildlife.

One evening Bruce and I attended a presentation on the local native culture at the park’s new Huna Tribal House, which opened in 2016 near the park service’s headquarters at Bartlett Cove.

Xunaa Shuka Hit, the new tribal house at Bartlett Cove in Glacier Bay, is modeled on the culture of the area’s native Tlingit residents. (Photo: U.S. National Park Service)

Glacier Bay is the ancestral home of the Tlingit, whose villages were destroyed by advancing glaciers more than 250 years ago. Traditionally, extended Tlingit families lived in a cluster of houses that made up a clan’s winter village. Daily life centered around a huge hearth in the middle of the room, with large fire pits.

A Tlingit carver inscribes traditional designs in the tribal house at Glacier Bay. (Photo: National Park Service)

Before the Little Ice Age, the Huna Tlingit found sustenance in the natural resources around the bay. But the local villages were overrun by glaciers in the 1700s. After the glaciers retreated, the native people reestablished fishing camps and seasonal villages in the bay.

Historical and ethnographic records were used to guide construction of the new tribal house, which is used for tribal events and cultural programs.

Bruce checks out his wingspan during our hike on top of Mount Roberts in Juneau (Photo: Diana Parsell)

We hopped a city bus to explore Douglas Island, across the strait from Juneau, and chatted with this local woman and her grandkids. (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Thanks to the local climate, Juneau’s downtown area had some of the prettiest flower boxes I’ve ever seen. (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Travel in Alaska, as we discovered in Juneau, is done mostly by air or sea. (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Really interesting, thank you. I visited Alaska in 2013 but missed the story of Eliza.

Thanks for writing, Rod. If I’d gone to Alaska in 2013, I too would not have heard or known much about Eliza Scidmore’s pioneering travels to the region. I was just getting started on research for a biography of her at the time, and I didn’t yet appreciate how significant her Alaska travels were. As I mentioned in the blog post, rangers at Glacier Bay are thrilled to learn more about her life so they can talk her up in visitor programs. So maybe on your next trip to Alaska you’ll hear about her!

Enjoyed the article on your the Alaska trip with Bruce. I traveled to Alaska several years ago with my husband, son, and parents, it turned out to be our favorite family vacation. Can’t wait to visit again. Looking forward to your upcoming book, so very proud of your accomplishments (hope you send me a signed copy), especially since I’m your favorite relative in Canton. Congratulations to your upcoming bestseller .