Eliza Scidmore, Fairchilds and D.C. Cherry Trees

Researchers, authors, students and history buffs gathered here last weekend for the 39th D.C. History Conference. I was there as a presenter on Friday, in a joint appearance with Washington author Ann McClellan.

Researchers, authors, students and history buffs gathered here last weekend for the 39th D.C. History Conference. I was there as a presenter on Friday, in a joint appearance with Washington author Ann McClellan.

The conference focuses on several major themes each year. The topics this year included the sesquicentennial of President Lincoln’s emancipation of slaves in D.C. and the centennial of the city’s Japanese cherry trees in Potomac Park.

I told the story of Eliza Scidmore, emphasizing D.C. connections that have come to light in my research. Ann McClellan, the author of two books on the Cherry Blossom Festival, described the efforts of a local couple, Marian (“Daisy”) and David Fairchild, who worked with Scidmore to procure the trees for Washington.

Daisy Fairchild with blooming cherry trees at “In the Woods,” the Fairchilds’ country home outside Washington (Photo: USDA)

Plant Explorer

David Fairchild was a botanist and plant explorer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He traveled the world looking for new foodstruffs and horticultural varieties to introduce in the United States.

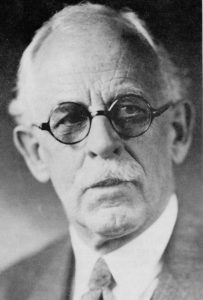

David Fairchild

During a trip to Japan, Fairchild met a Japanese expert on different varieties of cherry blossoms. Captivated by their beauty, Fairchild arranged to import a sample of the trees so he could study them.

The trees thrived at Fairchild’s home outside Washington. Their gorgeous display prompted his neighbors to purchase several hundred of the trees for the streets of Chevy Chase, Md. Those trees predate the ones in Potomac Park.

Fairchild and his wife (a daughter of Alexander Graham Bell) thought flowering cherry trees would be a perfect addition to the streets of downtown Washington. In particular, they envisioned an avenue of cherry trees along a new drive known as “the Speedway” (popular for carriage rides and motoring). The road ran through Potomac Park and along the Potomac river

Cherry Tree Champions

To garner support for the idea, David Fairchaild organized a publicity event on Arbor Day in 1908. He arranged to have local boys plant cherry tree saplings in schoolyards across the city.

Eliza attended the Arbor Day ceremony at Franklin School, where David Fairchild introduced her as a great authority on Japan. They became allies in trying to get cherry trees planted in downtown Washington — despite opposition from the city’s park officials.

Scidmore and David Fairchild found a chance to push their idea after William Howard Taft became president.

A few weeks after entering the White House, First Lady Helen announced plans to beautify an area of Potomac Park. Learning of her intent, Eliza Scidmore and David Fairchild teamed up to persuade Mrs. Taft to include cherry trees in her landscaping plans. Scidmore and Fairchild both sent letters to the White House. Scidmore wrote directly to Mrs. Taft, whom she knew as a social acquaintance.

First Lady Helen Taft loved going for drives along “the Speedway,” a riverside roadway that wound through Potomac Park. (Source: Helen Taft memoir)

Mrs. Taft took up the cherry tree idea at once. Her interest arose in part from her enthusiasm for motoring on “the Speedway.” She ordered her gardeners to acquire flowering cherry trees and get them planted as soon as possible, then wrote a note to Scidmore saying she’d done so.

Then, in a sudden turn of events, the project expanded dramatically. Eager to share the news, Scidmore described Mrs. Taft’s plans to a Japanese businessman, Jokichi Takamine, at a social event in Washington.

Takamine offered to donate 2,000 cherry trees for the project. Eliza Scidmore mediated the exchange with Mrs. Taft. In the end, Japan decided to send the trees as a gift from the mayor of Tokyo, Yukio Ozaki, as a gesture of friendship to the American people.

The 3,000 cherry trees sent to Washington in 1912 formed the nucleus of the stunning display we now enjoy every spring in the nation’s capital. About a million and a half people flock to Washington every year to see the trees in bloom.

Cherry blossoms in Washington with Tidal Basin and Thomas Jefferson Memorial in the background (Photo: Diana Parsell)