How to Be a Successful Biographer

Gandhi biographer Joseph Lelyveld, right, and Indian author M. J. Akbar at the Jaipur Literature Festival (Source: Manish Swarup/The Hindu)

What does it take to be a successful writer of biographies? The question discussed at a literary festival this weekend in Jaipur, India, caught my attention.

As a first-time biographer, I need to know the answer. There’s no formula for how to go about it, so am I on the right track?

Paul Beckett of The Wall Street Journal discussed the process with several authors. The panelists included biographers of such noted figures as Gandhi, Stalin, Obama and the Burmese protest leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

A Checklist

Based on the panelists’ comments, here are Beckett’s conclusions:

1. You have to be obsessed with your subject to write a good book. You need to get to know your subject so well that he or she “enters your subconscious.”

2. Forget the idea of a definitive biography. Even if your subject has been written about before, there will be angles that merit additional exploration. Be sure to bring something new to the table.

3. When possible, focus on the early years — on what formed your subject and led him or her along the path to notable achievement.

4. Try to find sources, in archives and elsewhere, that others have overlooked. There are bound to be fresh angles and insights.

5. Be ready for the long haul. One difference between a “journalistic” biography and a “scholarly” one, Beckett concludes, is the time it takes to write it. David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker and a biographer of Barack Obama, called writing biography is a “particularly strange” and “lonely” pursuit.

Guiding Motivations

So, how well does my biography project on Eliza Scidmore pass the test?

(No. 1) First is the issue of obsession. Does it count if you spend part of every day thinking about your subject? If you wake regularly in the night and reach in the dark to jot down random thoughts or lines of inquiry to pursue? (My research notebooks are full of yellow sticky notes I can hardly decipher.) Does it count if The Book seems to distract from other pursuits?

Research is helping me figure out Eliza Scidmore. On the other hand, she doesn’t visit me in my dreams, which I’ve heard several biographers say about their subjects!

(No. 2) As the first full-length biography of Scidmore, my book should be significant. And though I hope it’s definitive, I know that limits of time and resources. I expect others will come along years from now and flesh out her story further, since that’s how all knowledge advances — incrementally and collectively over time.

(No. 3) What I’ve learned so far about Scidmore’s family background and early years offers strong clues to her later success. There’s no question “nurture” had a major influence. But there’s also the fascinating issue of “nature” — how she was uniquely who she was, endowed with a combination of traits that made her exceptional in her time.

It’s the quest for psychological insight, more than anything else, that’s driven me to try to understand her so I can tell her story.

(No. 4) Another thing that keeps me motivated is knowing I’ve uncovered a good bit of previously “buried” information about her. That should make her story fresh and interesting.

The Long Haul

Finally, the ultimate question (No. 5): Am I up to “the long haul”?

Finally, the ultimate question (No. 5): Am I up to “the long haul”?

Besides juggling the huge volume of material, there’s the anxiety of trying to figure out all the dimensions of the story, how to best frame it, and what to do about obvious gaps of information.

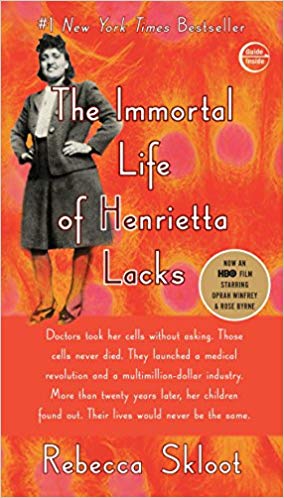

For inspiration, I think of Rebecca Skloot and how it took her 10 years to write her phenomenal best-seller, The Immortal Cells of Henrietta Lacks.

Laura Hillebrand spent a decade writing each of her popular books, Sea Biscuit and Unbroken. And Megan Marshall’s thick and engaging biography The Peabody Sisters (which I read last fall) was a 20-year project.

As so we circle back to No. 1: Doggedness. That’s what it takes for the long haul. Doggedness about the merit of the story and the need to tell it. That, and a lot of stamina.