Library of Congress Hosts Women’s History Forum

View of Great Hall at Library of Congress (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Today is the first Thursday of the month. That calls for packing my lunch so I can join the Women’s History Discussion Group at the Library of Congress.

We all crowd into a small conference room and sit around sharing ideas about research avenues for our various projects. Some of the tips are things that could take newbie authors and library outsiders, like me, years to figure out on their own. The three moderators — Janice Ruth (Manuscript Division), Barbara Natanson (Prints and Photographs Division) and Kristi Conkle (Humanities and Social Sciences Division) — bring a huge amount of knowledge to the group.

Fortuitously, I learned about the group right after I began going to the library to do research for a possible book on Eliza Scidmore.

I decided to check out the viability of the project in January 2010, when I faced the start of a new year with diminished job prospects. Due to the economic recession my freelance work had slowed down. The Christmas holidays were over. And of course, it was time for New Year’s resolutions. A lot of people vow to lose weight and head to the gym. I headed to the Library of Congress. (Hate the gym … though I do go there kicking and screaming.)

Unexpected Book Subject

I had stumbled on Eliza Scidmore while working in Southeast Asia. In a Jakarta bookstore I bought a reprint of the 1897 travelogue Java, the Garden of the East. It seemed to hold up well after a century. The writing was lively and the descriptions enticing. Curious about the author, “E. R. Scidmore,” I did an online search to find out what had taken him to far-off Java so long ago.

What a surprise to learn that the author was Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. And that her life was remarkable! Author of seven books. World traveler. First female board member at the National Geographic Society.

Most astonishing, I discovered it was she who introduced the idea of planting Japanese cherry trees in Washington, D.C. I had lived in the Washington area 30 years. I went nearly every year to see the cherry trees in bloom. How had I never heard of Eliza Scidmore?

Thus began my research quest at the Library of Congress to see if I could find enough material about her to write her biography.

Research Serendipity

Posted by all the library’s elevators were flyers about the Women’s History Discussion Group, so I followed the bread crumbs. The first person I met there was Dr. Peg Christoff, an Asian studies specialist who’s done work at the library for many years.

Peg is one of the smartest, warmest and most dynamic women I know. She was excited to hear that we had some overlapping research interests, since Eliza Scidmore traveled in Japan, China and other parts of the Far East. Immediately, Peg invited me to use the spare desk in her research office.

So now I’m an “independent scholar” with my own study desk at the Library of Congress. I love how that sounds. But as a non-academic, I usually just identify myself as an “independent writer.”

My writing desk at the Library of Congress (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Our office in the library’s Art Deco-style Adams Building is tiny, shabby and very retro. Two old desks with a pair of swivel chairs; bookcases, a metal filing cabinet, a wooden coat rack. The carpet is really nasty, and the plaster around the window frame is crumbling. It’s all in a space about the size of a pantry — and with no Internet connection. The room is so cramped that Peg and I often take turns working in the adjacent Science and Business Reading Room.

So why go there several times a week when I could work at home in my slippers? The main thing: several shelves of books reserved for my use, many of them highly specialized and not easy to find elsewhere.

I got an important lesson early on in what a difference that can make.

Map Treasure

The text of Scidmore’s books is available online. But seeing and handling a book in its original form can offer unexpected insight.

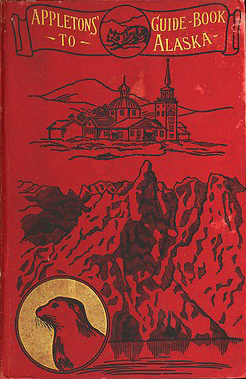

One day when I requested a first-edition copy of Scidmore’s 1893 guidebook on Alaska, it came with an unexpected treasure: Tucked inside a back flap was a long, thin fold-out map, printed in rich colors. It showed the exact route the steamers followed along the Inside Passage in the mid-1880s, when Scidmore went to Alaska for the first time.

Besides providing research leads, the monthly discussion group has increased my awareness of some of the challenges in writing about women from the past. “A lot of women’s history is buried in the records of the men in their lives,” I heard again and again.

Besides providing research leads, the monthly discussion group has increased my awareness of some of the challenges in writing about women from the past. “A lot of women’s history is buried in the records of the men in their lives,” I heard again and again.

But Eliza Scidmore’s father wasn’t famous, and she never married. Her brother George was a U.S. consular official who spent most of his career in Japan. Presumably his personal papers would reveal a great deal. But I learned that his property was lost at sea when the ship carrying it caught fire and sank.

I already knew from my research that few of Eliza Scidmore’s own papers have survived. So, it will be very interesting to see what I can find.